In January 2021, a group of 135 people representing funders, publishers, societies, and academic institutions gathered virtually to participate in the second CHORUS Forum. They came together to examine problems around connecting research data to content and learn more about existing and developing solutions. The purpose of the event was to advance ongoing collaboration across the scholarly community on these issues. Measured by the engagement and feedback from participants, we are pleased to say it was a success!

In January 2021, a group of 135 people representing funders, publishers, societies, and academic institutions gathered virtually to participate in the second CHORUS Forum. They came together to examine problems around connecting research data to content and learn more about existing and developing solutions. The purpose of the event was to advance ongoing collaboration across the scholarly community on these issues. Measured by the engagement and feedback from participants, we are pleased to say it was a success!

CHORUS Executive Director Howard Ratner kicked off the event by pointing to the unique role CHORUS has in bringing parties and perspectives together: “CHORUS has long been recognized for our work supporting open access, data, and transparency. Today we continue on that path with presentations from a diverse group of industry leaders who are driving change in this area. Our objective today is to take a look at the opportunities and challenges regarding data and software and spark some fresh thinking.” He noted that CHORUS will be convening additional Forums over the course of 2021 on an array of timely topics about the evolving research communications ecosystem.

Session One: Data Citations & Sharing

This session explored why data is an important asset, how it is currently managed as output, and what needs to change to make it more discoverable and reusable. Moderator Shelley Stall, Senior Director for Data Leadership, AGU, introduced a line-up of four speakers who reported on how they are creating an infrastructure that enables sharing in a way that advances open science.

Crossref Support for Research Data

Making research outputs easy to find, cite, link, assess, and reuse, is what Crossref is all about, so it’s no surprise that they’ve helped spearhead community initiatives on data sharing. Rachael Lammey, Head of Special Programs, Crossref, explained how using existing metadata, persistent identifiers (PIDs), and shared open infrastructure facilitates the collection and distribution of research data citations in a standard, scalable, and machine-readable way. This information becomes part of the bibliographic metadata that is routinely deposited in Crossref, where data citations are identified through DOI tags or structured references. The open data output is made available via APIs and Event Data which Crossref developed with DataCite to retrieve and expose activity around research data objects. Event Data is interoperable and it follows the Scholix framework for data citations (RDA uses the standard, too). Open data output is therefore discoverable through both Crossref and DataCite DOIs, and the data citation metrics collected through DataCite accrues in Event Data. Compliance monitoring is possible because the records also link to data licenses.

interoperable and it follows the Scholix framework for data citations (RDA uses the standard, too). Open data output is therefore discoverable through both Crossref and DataCite DOIs, and the data citation metrics collected through DataCite accrues in Event Data. Compliance monitoring is possible because the records also link to data licenses.

The result is that data citations are easily discoverable and usable by funders, publishers, institutions, and researchers — to reward, recognize, support, and replicate research. The schema is not bulletproof — there is a risk that information falls out during the workflow. According to Rachael, citation markup for publication types will be available later this year. Data Availability Statements will also be added to Crossref metadata before the end of 2021.

Connecting Research, Identifying Knowledge

As the Executive Director of DataCite, an organization that provides persistent identifiers (PIDs) for research data and other research outputs, Matthew Buys described PIDs (and the associated metadata) as “…essential component[s] for the implementation of the FAIR principles,” and spelled out  their dynamic role:

their dynamic role:

- Findable – standard metadata connected with PIDs makes research data findable

- Accessible – Resolvable worldwide with every internet browser, the DOI remains the same even when the URL associated with the research object is changed

- Interoperable – PIDs share standard vocabularies and link to one another in their metadata records

- Reusable – enables researchers to cite sources with confidence and receive proper credit when their work is reused

DataCite connects PIDs in standardized ways to maximize access to outputs via researcher repositories, institutions, or funders, for discovery and impact assessment. DataCite Commons, a web search interface for the metadata and PIDs associated with research publications and data (Crossref, DataCite), people (ORCID), and research organizations (RoR) was launched last year. DataCite maps these related identifiers in a PID Graph. By advancing and surfacing relationships (e.g., authorship, affiliation, reuse), the PID Graph helps follow the trail of research from dataset, to article, to institution, and so on. It thereby enables discovery through these connections, leverages usage and citations, and enables impact assessment.

With this infrastructure in place, additional metadata contributions will improve reuse and discovery. Adding rights information, for example, will help researchers and harvesters learn if they can reuse the data. Adding abstracts and other descriptive information will enable mining for emerging trends without singling out controlled vocabulary terms. Putting data citations in structured form makes them machine readable, which creates the potential for scaling up on a massive scale, through artificial intelligence (AI) applications.

Data citation and sharing during article publication

Springer Nature’s 2019 report, The State of Open Data, explored researcher views on data citations and sharing. According to Data Curation Manager Varsha Khodiyar, nearly 7 in 10 researchers surveyed said that availability of full data citations would motivate them to share data. More than half of the respondents also cited the following reasons as compelling: increased impact and visibility, co-authorship on papers, public benefit, journal/publisher requirement, greater transparency and reuse, and funder requirements. At the same time, more than a third of them said they had significant concerns about data misuse, sensitive information or permissions required, not getting proper credit or acknowledgement, uncertainty about copyright, licensing, permissions, and the costs, or how to organize and present data for reuse.

Varsha asked and answered the question, “How do we bring the good dataset practices we’ve developed to journals?” Journal policies are a good starting point to get authors in the habit of citing and referencing datasets for new and reused data in their manuscripts. Another way is to encourage authors to share data in community-initiated, discipline-specific repositories and provide descriptive information that can form the data availability statements. Allowing the citation of public datasets in reference lists/bibliographies is also a best practice.

Another tactic is providing hands-on support to researchers and editors as they navigate new data workflows. Optional curation services are offered to tackle issues regarding data integrity, fix errors, provide advice on presentation and linking, and improve dataset FAIRness. Nature Research Academies provide forums for discussion of data sharing concerns.

Springer Nature’s strategy also includes active support for nascent initiatives to develop a shared open infrastructure around data citations that enable FAIR principles. Building consensus among organizations involved in the data literature ecosystem advances connection between data and research literature and encourages community-endorsed norms and data sharing standards.

How do we get there?

DataSeer Project Lead Tim Vines reported on an initiative that enables scaling up data sharing on a massive scale. He cited two studies (a 2019 Pew Research Center report and Soderberg, Errington, and Nosek’s 2020 paper) that document how the availability of data engenders trust in science by public and research communities. His point was that regardless of whether the respondents were interested in reproducing the research, they agreed that data availability inspires confidence.

Tim explained that leading authors through the data sharing process is effective individually, but not practical given the enormity of the task at hand. Only artificial intelligence (AI) can do it on the massive scale needed for a paradigm shift.

The service DataSeer has developed uses natural language processing to identify datasets by assessing stereotypical references, surface the links between data and articles, and determine which ones have been shared. A report is generated with suggestions for improving the data citations and a recommendation for the most suitable content-specific repository. At the end of the process, DataSeer issues a Certificate of Open Research Data. This serves as a machine-readable Data Availability Statement, which makes shareable datasets publicly available and points to the remainder. A PID is assigned and the metadata goes to Crossref; Plans are in the works for a Scholix hub.

This resource can be used for auditing data sharing for a corpus of documents, articles, or reports to demonstrate compliance with open data policies. DataSeer conducted a proof of concept by assessing PLOS One publications between 2016 and 2018. The results, which will be published, showed increasing data publication over the course of the study period. More pilots are being conducted with publishers and preprint services to explore other use cases.

Session Two: Challenges and Progress with Data as a Key Asset for Funders and Academia

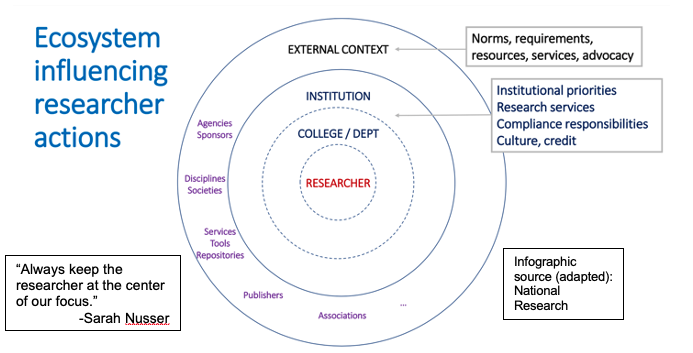

Representatives from funders and academic institutions presented on what their organizations have been doing to recognize data as a key asset, minimize the burden for researchers, and automate data management for maximum accuracy and impact. Howard Ratner moderated the session, which explored how to help researchers assess their data citations and how to incentivize them to share them responsibly.

Open science and FAIR data in Horizon Europe and beyond

Konstantinos Repanas, Policy Officer at Open Science Unit, Directorate-General Research & Innovation, European Commission, began with a brief overview of the Commission’s role as a policy maker (enacting legislation), funder (setting requirements), and capacity builder (funding enabling projects) for advancing open science. Sharing knowledge and tools (as early as possible) among researchers, their communities, and with society at large improves the quality, efficiency, and creativity of research and trust in science. It also tackles the reproducibility crisis, boosts the response to societal challenges, enables more collaborations, sparks new findings, and reduces inequalities.

Starting in 2008 with an open access pilot for publications, the Horizon Europe framework, as part of its Horizon 2020 initiative, subsequently strengthened OA obligations and required responsible data management plans (DMP) in line with FAIR. Looking ahead, Horizon 2021 will continue to expand the role of open science (OA, DMP, and citizen engagement) in the evaluation of proposals, grant agreements, and reporting. Konstantinos shared that a Commission governing principle is that data should be “as open as possible, and as closed as necessary.” All data must be in line with FAIR, but there are some valid reasons (for example, privacy) for not fully opening data.  DMP should be living, machine-readable documents that cover all related research outputs, and are established early and regularly updated. Grantees are required to deposit their data in repositories that provide PIDs, link their data to the publications they underpin, and ensure OA under CC BY or CC0 license. Stringent requirements will also be enacted with respect to other outputs in line with FAIR principles. “Researchers need quick and unrestricted access to multiple data sources to accelerate their research. FAIR is an essential component in this.”

DMP should be living, machine-readable documents that cover all related research outputs, and are established early and regularly updated. Grantees are required to deposit their data in repositories that provide PIDs, link their data to the publications they underpin, and ensure OA under CC BY or CC0 license. Stringent requirements will also be enacted with respect to other outputs in line with FAIR principles. “Researchers need quick and unrestricted access to multiple data sources to accelerate their research. FAIR is an essential component in this.”

Mainstreaming FAIR across the research community as funders across the EU and beyond are incorporating the principles into policy and requirements is needed to increase compliance. Determining how to help researchers evaluate the FAIRness of a dataset is an important first step. According to Konstantinos, a stumbling block is the scarcity of comprehensive and comparable evaluation mechanisms/metrics for what until now have been abstract or imprecisely defined requirements. He touched on the work they are doing with initiatives to fill the gap:

- The RDA Working Group on the FAIR data Maturity Model has delivered a set of indicators, priorities, and guidelines to enable researcher self-assessment and funder evaluation.

- Led by RoRI, the FAIRware initiative is working with funders across the EU, UK, US, and Canada to develop new open-source tools to allow assessment of research output FAIRness, implement global standards for FAIR certification of repositories, and build pool of existing knowledge (e.g. WorkflowHub).

- FAIRsFAIR is developing F-UJI, a tool that automates FAIR data assessment, and FAIRAware, an online questionnaire to assess researchers and data managers knowledge of FAIR requirements.

Public Access Program at NSF: Current State and Next Steps

To provide context for where the National Science Foundation (NSF) public access program is heading, NSF Advisor for Public Awareness Martin Halbert

recounted its progress since 2013. That was when the US Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) issued a directive calling for the direct results of federally funded scientific research (peer reviewed publications and digital data) to be made publicly available and directed agencies issuing more than $100 million in annual grants to develop plans to achieve this objective.

In 2015, NSF rolled out their Public Access Repository (PAR) 1.0 to reach the OSTP objectives and broaden access to NSF-funded research publications, data, and other products that built on current policies and practices and leveraged the resources of other federal agencies, universities, research institutes, and private initiatives. Its infrastructure comprises several interacting systems at the NSF, the Department of Energy’s Office of Science and Technical Information, and a number of external organizations, such as CHORUS, Crossref, ORCID, DataCite and others. PAR 1.0 gives researchers choices about how they use the system: they can either enter the metadata for their publications, or auto-populate it using the DOI. They can deposit articles as PDF/A files or point to download locations through the DOI.

Over the past year there has been incremental progress to identify best practices and coordinate efforts of federal agencies, for example, looking at desirable characteristics of repositories and surveying which PIDs are used. Work was completed on a major project to accumulate data in trusted repositories. PAR 2.0 (to be released in 2021) will make it easier for researchers to deposit and assign PIDs to datasets. Partnerships with external organizations such as Figshare, Dryad, and disciplinary repositories, are being established and expanded. As part of this, NSF will continue to maximize adoption of best practices, coordinate on features, and think about the overall ecosystem with other federal agencies and external organizations.

Is this what FAIR data looks like?

Susan Gregurick, Associate Director for Data Science, NIH, proudly acknowledged the progress already made to make NIH-funded research data outputs FAIR, with the involvement of public/private partnerships, “Kudos to Crossref and DataCite for their PIDs, making datasets searchable, analyzable, and computable. A lot of work is going on to make it possible and take next steps.”

She then focused on the “next steps” laid out in the Final NIH Policy for Data Management and Sharing, which was released late in 2020 to become effective early in 2023. Among its requirements, the policy will require all NIH-funded researchers to submit the Data Management and Sharing (DM&S) plan as soon as possible and before the end of the performance period.

The work ahead will assist researchers to identify and select suitable repositories, guide development of agency-supported repositories, help federal agencies evaluate unaffiliated repositories, and guide such repositories to align with agency policy. NIH funding is now available to support the development of external repositories that commit to making data FAIR. The agency identified the characteristics of suitable repositories and will soon formalize the requirements. These include repositories that assign PIDs, plan for long-term sustainability, accompany the data with metadata, provide mechanisms for curation and quality assurance, ensure free and easy access to data, define broad and measured terms of reuse, offer clear use guidance measures, use documented security and integrity, warrant confidentiality, employ common formats, track provenance, and supply a retention policy. Additional characteristics were articulated for the preservation and sharing of human participant data to ensure fidelity to consent, participant privacy, sovereignty of data (for tribal nations), comply with data control and use restrictions, control and audit downloads, address terms-of-use violations, use a request review process, and plan for a breach.

NIH is also developing best practices in data resource management and the use of metrics to understand data use and utility as it moves through the stages of the data resource lifecycle — when data is acquired, curated, aggregated, accessed, analyzed, and preserved by an active data repository and platform.

This work continues as a result of collaborations that Susan termed as “coopetition.” Public and private organizations compete on specific/unique features (e.g., dashboards, visualization, analytics, and linked data) and collaborate on common/shared goals (e.g., core metadata, identifiers, and authentication).

APARD: A Guide for Change in Research Universities

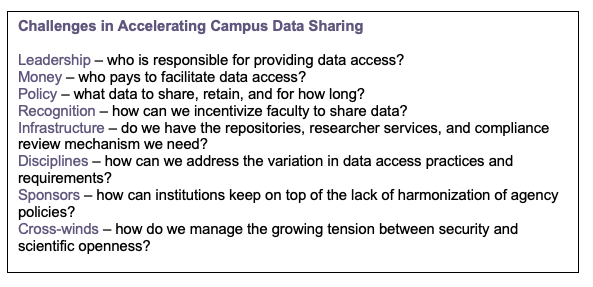

Sarah Nusser, who is the Iowa State University research officer but spoke in her capacity as the Co-PI of the Accelerating Public Access to Research Data (APARD) project, gave an update on her presentation from the July 30th CHORUS Forum. Significant progress has been made in the intervening months to align data-sharing policies and practices across academic institutions,  to galvanize the community and broaden participation in the initiative, and to support and provide input through an implementation guide.

to galvanize the community and broaden participation in the initiative, and to support and provide input through an implementation guide.

The APARD Guide is envisioned as a resource for administrators to accelerate progress and articulate how research outputs are aligned with the research institution’s mission. It will outline the major steps of developing support systems for data sharing. A pre-publication draft will be shared at the second annual APARD Summit in March.

The APARD project is supported by grants from NSF (and augmented by NIH), and led by the Association of American Universities (AAU) and Association of Public & Land-grant Universities (APLU). Thirty institutions were initially involved, but participation broadened to include 75 more over the past year. Despite the challenges of supporting data sharing, universities are increasingly recognizing that public access to research data aligns with their own missions:

- Accelerating discovery and innovation advances science and use of scholarship by their faculty.

- Increasing rigor and public trust addresses reproducibility concerns and makes faculty research more accountable through transparency.

- Creating consistency in data policies across campuses helps compliance with sponsor requirements and increases the likelihood of future grants.

Sharing the example of a successful implementation of a steering group structure at Virginia Tech, Sarah cautioned that the flow of progress is not always linear in one direction. As more universities take part, however, there will be more unique examples that can be included in the evolving Guide.

Valuing the importance of data: New opportunities

Julia Lane, Co-founder of the Coleridge Initiative, has been part of US public access policy development since early days. She observed that we are now in “a unique period to take advantage of opportunities to advance open science because the technology and systems are mature enough, and legislative and funder mandates  have caused shift policies towards leveraging data as a strategic asset.”

have caused shift policies towards leveraging data as a strategic asset.”

Julia reviewed the history of legislative and funder actions and policies regarding data and outreach for community input on how to identify valuable data for evidence building. She shared with Forum participants that the incoming US science leadership had already shared their data priorities on Inauguration day (health, racial injustice, climate change, the economy), sending a clear message on the role of evidence-based science in the new administration.

The success of the move to open science has spotlighted a problem that must be addressed: How can we identify what is valuable evidence out of the resulting sea of data? The flip side of people/agencies making more and more data open, is a “vomit of data.” Some of it is valuable and some isn’t. An important next step is to “sort the wheat from chaff.”

As an economist, Julia said she has given a lot of thought to creating incentives. Pointing out that Amazon and Yelp both have built successful incentive-based systems in which users recommend valuable information that enable future users to efficiently narrow future searches. In the research data world, there isn’t an equivalent – you can search research by subject areas, authors, and other terms, but the citations don’t have underlying recommendation engines that rank them. Moreover, refining the search works for articles but not for the datasets that are contained in the articles. Artificial intelligence can be used to surface datasets in publications that are “hidden in plain sight.” But the better the information that goes into the metadata, the more value we can harvest.

Creating an incentivization system to encourage better contributions from authors is at the center of the Coleridge Initiative’s mission. Julia shared the results of a feasibility study which used CHORUS to identify OA publications containing data and identify the funders. The data was categorized and analyzed to create an assessment framework to assign usage scores that reflect the relative value of datasets to community (usage, publications, authors, institutions, relation to other datasets) relative to agency mission. Such a data usage scorecard, powered through AI, will create a market signal to stakeholders that incentivizes them to contribute information. Julia said the work so far has validated the proof of concept, and the initiative is sponsoring a Kaggle competition as the next step.

What’s Next?

A lively exchange among the panelists about how to take data citations and sharing to the next level began following the presentations. Actively demonstrating “coopetition,” they shared some key takeaways:

- Funder policies make a big difference because they motivate researchers (who want to secure additional grants) to comply and help them understand what’s expected of them.

- It would be highly beneficial to develop an altmetric score that measures the performance of datasets, evaluates their value to the community, and gives credit to researchers.

- Automating the process minimizes the burden to the researcher, enhances the accuracy and quality of metadata, and will enable implementation and monitoring on the scale needed to significantly advance open science.

Not all of the participants’ questions had been addressed when time ran out. CHORUS is responding to unanswered questions individually, and hopes that the community’s hive mind will further these conversations.

The third CHORUS Forum on Making the Future Work is scheduled for 23 April 2021. Please save the date! More details will be released soon.